#398 | Universal Life Outside the Lines

Over the past few weeks, two stalwarts of independent distribution – John Hancock and Pacific Life – have released new versions of their respective best-selling Indexed UL products. At first blush, the two products don’t have much in common. John Hancock’s Protection IUL series is built to deliver ultra-low illustrated premiums. Pacific Life’s Horizon IUL series is designed for strong accumulation performance. Unlike many Universal Life products that are flexible enough to stretch outside of their primary design goal, these two products are singularly focused. Protection IUL is saddled with an enormous 35% premium load, high enough to strangle any real accumulation potential, and PacLife’s illustration software throws an error code if you try to do a minimum premium solve on Horizon IUL. The venn diagram on these two products has essentially no overlap.

However, Protection IUL and Horizon IUL have far more in common than you might think. Both products rely heavily on what might be termed “non-traditional” product elements that don’t follow the usual logic or math of traditional life insurance products. They are engineered specifically for certain outcomes. In the case of Protection IUL, the non-traditional element is the Policy Value Credit, which I’ve written about in previous articles on Protection-series John Hancock products, most recently the refreshed Protection UL. And for Horizon IUL, the non-traditional element is the Persistency Credit.

The engineering of both the Policy Value Credit in Protection IUL and the Persistency Credit in Horizon IUL is remarkably similar. The Policy Value Credit follows the slope of the COI curve – as COIs increase, so does the Policy Value Credit. It looks like it is essentially a mechanism to offset COI charges and the formula is guaranteed in the contract. But unlike COIs, the Policy Value Credit isn’t denominated by Net Amount at Risk. If you put the maximum non-MEC premium into the policy or the bare-bones minimum premium, the Policy Value Credit doesn’t change even though the underlying COI charges do based on Net Amount at Risk. The PVC only reacts in fringe scenarios where the policy is in corridor or lapsing. Take a look at the PVC on a 45 year old Preferred Male for a $1M DB along with the COI rate per $1M of NAR:

What makes the PVC so interesting – besides the fact that it essentially creates a non-guaranteed COI slope without using that exact term – is that the PVC is a fixed benefit unrelated to the performance of the base contract. It’s a core product element that almost seems to operate independent of the core product and yet it drives a substantial portion of the overall value. The same is true of Pacific Life’s Persistency Credit, except that the mechanics of the Persistency Credit are entirely independent. Unlike other persistency credits, this one isn’t paid out as a percentage of assets. It’s a pure dollar amount. And no matter how you fund or illustrate a product with the Persistency Credit, the dollar amount paid out under the Persistency Credit is always the same.

When I first wrote about the Persistency Credit, I called it an “embedded tontine” because that’s what it looks like. You buy the policy, charges are deducted, some people lapse (and die) and the ones who survive get an enormous long-term benefit that is far in excess of what is justifiable simply on simply the basis of earned interest over time. In Horizon IUL, for example, a fully blended contract on this same cell has $47,804 in charges over 15 years and pays a little under $440,000 in credits from years 20 through 50 for an IRR of 7.45% – and that’s assuming that every penny of the $47,804 goes to fund the Persistency Credit, which it does not. There is, in other words, a mechanism built into Horizon IUL that delivers a 7.45% return regardless of the actual headline illustrated rate for the product. Like I said, it feels a lot like an embedded tontine.

Both Pacific Life and John Hancock have a long history of over-engineering their life insurance contracts with newly created mechanisms that seem to fly in the face of typical insurance conventions. Hancock was doing something like the PVC as far back as the old Performance UL policy, although it worked in reverse. PacLife was the first company to use charge-funded multipliers and did it with a wonky fixed-charge structure that, as with the Persistency Credit, was essentially unrelated to the performance of the policy itself.

Features like the Pacific Life’s Persistency Credit and John Hancock’s Policy Value Credit are essentially products inside of products. These sorts of structures can be extremely powerful for competitive positioning, but they also introduce unique risks and unknowns that distributors, agents and certainly end customers don’t know exist. Case in point – the new John Hancock Protection IUL 24.

The irony about the new version of the product is that John Hancock changed virtually everything in the policy except the Policy Value Credit. The headline for the new product is that it offers lower illustrated premiums than the previous version, Protection IUL 22R. The most obvious way that it gets there is by juicing the illustrated rates. Protection IUL 22R (and previous product versions) had a substantial asset-based fixed interest bonus that has been trimmed back in the new version. Take a look at the difference on a 45 year old Preferred Male:

Where’d the benefit go? Into the crediting rates. In the previous product, the Select Capped account had a 9% Cap with a 5% bonus and a maximum illustrated rate of 6.08% (including the bonus). In Protection IUL 24, the same account has a 9.6% Cap with a 15% bonus and a maximum illustrated rate of 7.02%. Like many other carriers, John Hancock uses a hypothetical Benchmark Indexed Account to provide air cover for more aggressive illustrated rates in the other accounts. In the new product, the maximum illustrated rate for the hypothetical BIA is a whopping 7.27%. However, John Hancock eliminated the version of its Barclays Global Multi-Asset account with the fixed bonus, meaning that there is no longer an illustrated benefit for choosing the engineered index. That’s a welcome change for the better.

In short, John Hancock shifted value out of the fixed interest bonus and into the illustrated rate, with the net effect being better overall illustrated performance. For the same cell as above, the illustrated level premium dropped from $7,341 to $6,948, a 6% reduction. The difference is even more stark for shorter premium solves because more account value is eligible to receive higher illustrated credits earlier in the life of the contract. For a 10 Pay solve, the new product is 9% cheaper. And on single premiums (1035 exchange), the difference is nearly 11%.

Back in the good old days of Guaranteed UL, cheaper premiums were cheaper premiums were cheaper premiums. Rarely was there a tradeoff for the consumer. Instead, the tradeoff was for the life insurance company. Cheaper premiums meant more risk and more dependence on interest rate, mortality and lapse assumptions for profitability. But in modern Universal Life policies like Protection IUL, the tradeoff almost always goes back to the customer. If premiums are cheap, that’s because the client is taking more risk – and the stock illustration does a great job of showing the cheaper premiums but not necessarily the increase in risk.

The tradeoff for Protection IUL 24 is the loss of the fixed interest bonus and a meaningful uptick in long-term Cost of Insurance charges. The fixed interest bonus was a stabilizing feature of the product because it was obviously credited regardless of indexed performance. Long-term Cost of Insurance charges matter because they bite in scenarios where the policy has underperformed and/or the policyholder lives a long time. The net effect is that Protection IUL 24 is more punitive when it underperforms than Protection IUL 22.

At a 3% illustrated rate, the level pay premium for Protection IUL 22R to endow the policy will cause a lapse in the mid-90s on Protection IUL 24. Why? Because the PVC didn’t really change but the COIs did. The net cost of protection to the customer, therefore, went up. If the cost of protection isn’t offset by increased performance, then the policy lapses with the same premium. It’s simple, but not obvious. And certainly not obvious if you were just to look at the marketing materials for the new product.

By contrast, Pacific Life’s update to Horizon IUL is focused almost entirely on the Persistency Credit. When I first wrote about the Persistency Credit in its initial form in PacLife PDX 2, Pacific Life was very coy about what it was or how it worked. They barely acknowledged that it even existed. This update brings it front and center. PacLife’s marketing material talks about the three different versions of the product – Balanced, Long-Term Performance and Enhanced Early Surrender Value – as being the same core product but with three different Persistency Credit structures designed for different goals. The Persistency Credit now isn’t just background noise. It’s the driver of the product.

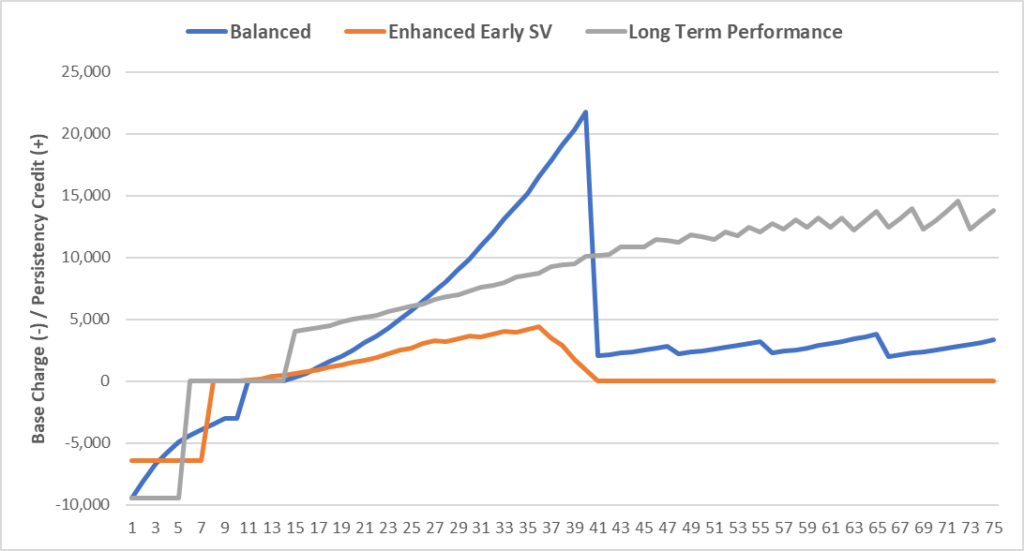

Run a few illustrations on Horizon IUL 2 and it won’t be hard to see what PacLife is doing with these three product variants. Take a look at their respective initial charges and Persistency Credit payoffs. And remember, unlike the actual life insurance product, this Persistency Credit product is not dependent on policy performance. It’s a pure cash in/cash out structure. The negative numbers for each line shows the Base charge and the positive numbers are the Persistency Credit.

If you run the IRR on each line for pure input/output, Balanced clocks in at 5.86%. If that strikes you as low, consider the fact that this cell has a $19,680 Target premium. Carriers typically amortize Target plus Override – which is around $26,000 in this case – through the Base charges over the first 10 years. If you take $26,000 out of the policy charges, the IRR for Balanced jumps up to just over 9%. The same exercise for Long Term Performance pushes the IRR to over 10%.

Therein lies the power of the Persistency Credit. Taking commissions into account, each dollar that goes to fuel the Persistency Credit earns north of 9% – way, way higher than the illustrated rate for the product. Way higher than the illustrated rate for any Indexed UL product. The Persistency Credit isn’t an Indexed UL product. It’s an embedded tontine- and it delivers tontine-like returns as long as you stick around and live long enough to get them.

Actually, the numbers are probably even higher for Balanced and Long-Term Performance, but it’s hard to effectively parse out what part of the Base charge goes to cover commissions and what part goes to fund the Persistency Credit. Typically, that sort of thing is easy to do in a PacLife policy because commissions are adjustable. You can just blend the contract and look at the difference between the commissions and the Base charges to get a ratio. For every dollar of commissions, there will be 1.7 dollars (for example) in total Base charges. That’s exactly what it is for PacLife FlexVenture UL, which doesn’t have the Persistency Credit. Easy enough.

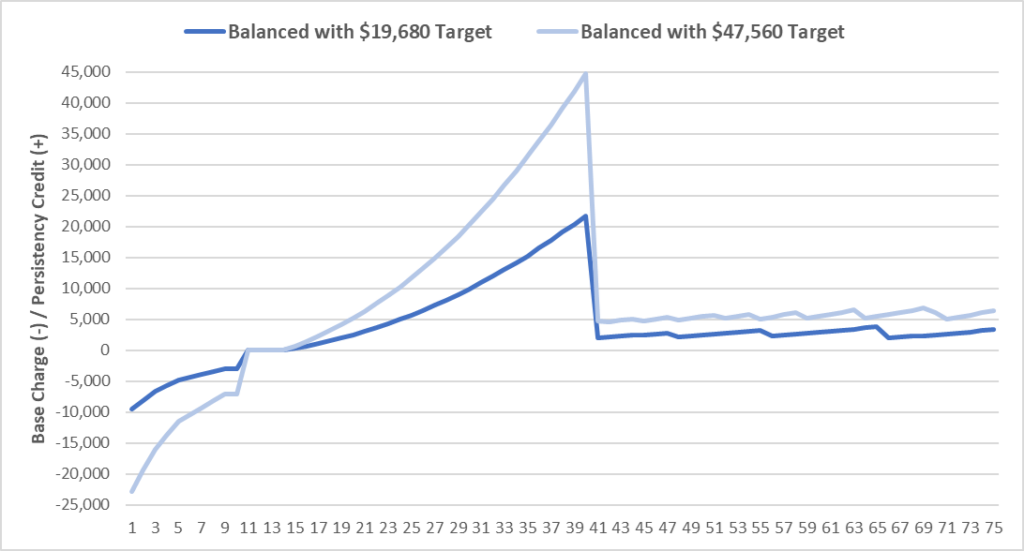

But for this contract, the ratio of Base charges to commissions is much higher – on the order of 2.6 dollars – and the size of the Persistency Credit increases as commissions increase. Take a look at Balanced with a Target of $19,680 versus Balanced with a Target of $47,560*.

If you run the IRRs on the pure Persistency Credit component, the two cash streams are actually pretty similar, both with and without taking commissions into account. The higher Target structure lags by about 50bps in terms of pure IRR, but that’s not the right way to look at it. Think of the Persistency Credit as a magical money machine that delivers a guaranteed IRR on contributed cash that is much higher than the base contract after taking commissions into account. The higher Target design puts way more dollars into the Persistency Credit than the lower Target design.

As a result, the performance of the higher Target design is disproportionately attractive versus what it would have been without the Persistency Credit. In the long-run, the additional drag from higher compensation is around 15bps. The figure for FlexVenture UL (no Persistency Credit) is closer to 30bps. You might even go so far as to say that Pacific Life is incentivizing higher commissions by providing an offset to illustrated performance from higher funding of the Persistency Credit. It’s bizarre. The Persistency Credit is independent of every other policy element, so then why is it linked to commissions?

The other wrinkle to the Persistency Credit is just that – persistency. You can see the different persistency scenarios playing out across the three designs. Balanced amortizes the Base charge over 10 years with a declining schedule and pays the vast majority of the Persistency Credit from years 15 through 40, with a low residual trail. Long Term Performance has the same Surrender Charge schedule as Balanced but front-loads the Base charges over 5 years and defers the Persistency Credit for as long as possible, starting in the 15th year and gradually increasing over time. This is tontine economics at work. The more the charges are front-loaded and the longer the benefit is deferred, the greater the overall potential value for those who stay. And that’s exactly what we see between Balanced and Long Term Performance.

Enhanced Early Surrender Value plays the opposite side of the dynamic. The Surrender Charges are about half of Balanced and Long Term Performance, which tells you right out of the gate that the subsidization for the Persistency Credit will be lower because lapsing policyholders will be more common and will get more back when they lapse. The Persistency Credit also starts in year 11, earlier than the other designs. As a result, the economics on EESV are much less compelling. The IRR without taking commissions into account is just under 2%. After deducting commissions, it’s closer to 5%. EESV looks a lot like FlexVenture UL in terms of pricing and surrender charges. Despite the name, it’s essentially what PacLife policies looked like prior to juicing the illustrated returns through the Persistency Credit. A better name for EESV might have been “classic” or “normal.”

The fundamental challenge posed by both the Persistency Credit in PacLife’s Horizon IUL series and the Policy Value Credit in John Hancock’s Protection IUL series is that they don’t play by the normal rules of life insurance policies. These are Universal Life contracts but the policy structure is a container for other things as well – things that the vast majority of distributors, agents and certainly consumers don’t even know are in the box and will only find out if things don’t go as planned. The onus is on producers to spot the fine print and understand the underlying assumptions that drive the illustrated benefits from these sorts of features. And that’s a very, very tall order.

Is there any obligation for Pacific Life and John Hancock to maintain these non-guaranteed elements? Of course not. These are non-guaranteed elements, after all, event though both companies have an admirable history of maintaining non-guaranteed elements. Would anyone even noticed if they did change? If the client didn’t know they were there to begin with, then how could they? I can imagine policy reviews for these contracts happening in 30 years and a befuddled young advisor trying to unsuccessfully piece together the puzzle of why the policy has performed the way it has. Good luck.

My sense is that there will be more and more features like these making their way into life insurance contracts. They deliver the goods in terms of illustrated performance and fit within the current regulations and guidelines. They play on the fact that Universal Life is basically a container for product elements and you can fit a heck of a lot of things into the container.

But there’s a bigger question at play – is it good? Consider that the major mutual companies pride themselves on persistency and talk about how persistency drives policyholder returns. With the Persistency Credit, the opposite is true. High persistency will make the Persistency Credit collapse under its own weight. Similarly, traditional permanent life insurance is built around the concept of risk transfer but, with the Policy Value Credit, the carrier has the ability to disproportionately penalize poor performance without having to change any non-guaranteed elements.

Adding things to permanent life insurance can be very beneficial. No one thinks that the proliferation of accelerated death benefit riders is bad for policyholders**. But these new features aren’t benefits. They’re just tradeoffs. There are situations where they can be beneficial and other situations where they can be punitive. And unless you really, deeply, fully understand how these new tradeoffs work, the wise path might be to avoid them altogether.

*The lower Target is using Option 1 with all Base coverage. The higher Target uses Option 2, which allows for much higher compensation in the PacLife world, with an immediate switch to Option 1.

**Some of these accelerated death benefits can, however, be badly built and executed. But the benefits themselves are additive to policyholders in that they provide another way to use life insurance.