#389 | VUL & The Tax Cost Ratio

Full Article

Life insurance is often – and often problematically – characterized as being “tax free.” That isn’t strictly true. The cash value itself is taxable upon sale. That’s consistent with other financial instruments. If you own a stock that has grown substantially for 10 years and have never received any distributions, have you been taxed on those gains? Nope, you’re only taxed when you sell the stock. If you own a life insurance policy and never receive any distributions, do you pay tax on the growth of the account value? Nope, you only get taxed when you “sell” it through a surrender or withdrawal. Tax deferral isn’t a feature of life insurance – it’s a logical function of the fact that gains haven’t been realized. Life insurance isn’t tax advantaged. It’s taxed appropriately.

However, that doesn’t mean that it’s taxed identically to the alternatives. One apparent advantage of life insurance is that unrealized gains aren’t treated as imputed interest as in a bank CD. That’s not a carve-out advantage for life insurance but a reflection of the fact that unlike a CD, life insurance has policy charges that go against the earned interest. If interest in life insurance was made taxable, then would policy charges be made tax deductible? Should the client only be taxed on net policy growth? Does that mean clients get tax deductions when their policy values decline and nears lapse? Taxing the annual build up in policy cash value would be virtually impossible to execute without creating some bizarre tax scenarios.

The singular tax advantage of life insurance is that the payment of a death benefit is not treated as a taxable sale per Section 101 of the IRC as long as the policy qualifies as life insurance for tax purposes by maintaining the appropriate relationships between premium, cash value and death benefit over the life of the contract. A death benefit that is comprised of 40% premium, 50% interest gains and 10% Net Amount at Risk (the actual insurance component) is still exempt from taxation as long as it conforms to the applicable tax requirements. That’s the beauty of life insurance.

But the magic of life insurance is that the policyholder has the ability to collateralize the cash values without tax incidence because the ultimate security for the policy loan is the tax-free death benefit. The tax-free nature of the total death benefit is essentially extended to the individual components of the death benefit, including interest gains that would otherwise be taxable upon policy surrender or withdrawal. To draw the analogy back to other investments, a death benefit is not a “sale.” It’s a non-taxable disbursement event.

As a result, cash value collateralization – either by policy loans or external loans – isn’t a taxable event as long as the death benefit remains in-force. That’s consistent with tax treatment for the collateralization of other assets, such as real estate and equities, that have embedded gains. The moment the death benefit disappears through a policy lapse, the gains are taxable because the policy is surrendered. Life insurance tax treatment is perfectly logical. How else could it work? Consider that Canada, which is often pointed out as a jurisdiction that taxes inside build up of cash values, employs the same basic tax logic except that cash value collateralization does count as a taxable realization of gains. They’re essentially forcing a taxable realization where a realization doesn’t actually exist. That’s a tax policy choice to specifically target life insurance cash values in a way that other assets aren’t targeted.

A more accurate characterization of life insurance is that it offers the ability to have control of tax incidence. It can be used for tax deferral if proceeds are withdrawn or surrendered. It can provide tax-free policy loans as long as the contract stays in-force. It ultimately delivers a tax-free death benefit. And if you want to change the tax characteristics of the policy, you can make it a Modified Endowment Contract or, as we’ve seen with some offshore designs, have the policy purposely fail Section 7702. The point is that the policyholder has complete control of how, when and how much tax is paid – except in the event of a death, in which the entire thing is tax-free anyway.

Mutual funds and ETFs theoretically allow for tax control in that the investor can decide when to sell and pay tax on gains. But that’s only part of the story. Funds make distributions and those distributions are taxable. Equally as important, funds have turnover in their assets that also generates tax liabilities that are passed to the fund investors. Some funds have more taxable distributions and more turnover than others. The headline total return of a fund is important but so is the taxable nature of the way the fund achieves its returns. For high income earners who would otherwise prefer to defer taxes (or avoid them altogether), the average annual tax drag of a fund is a real determinant of after-tax long-term returns.

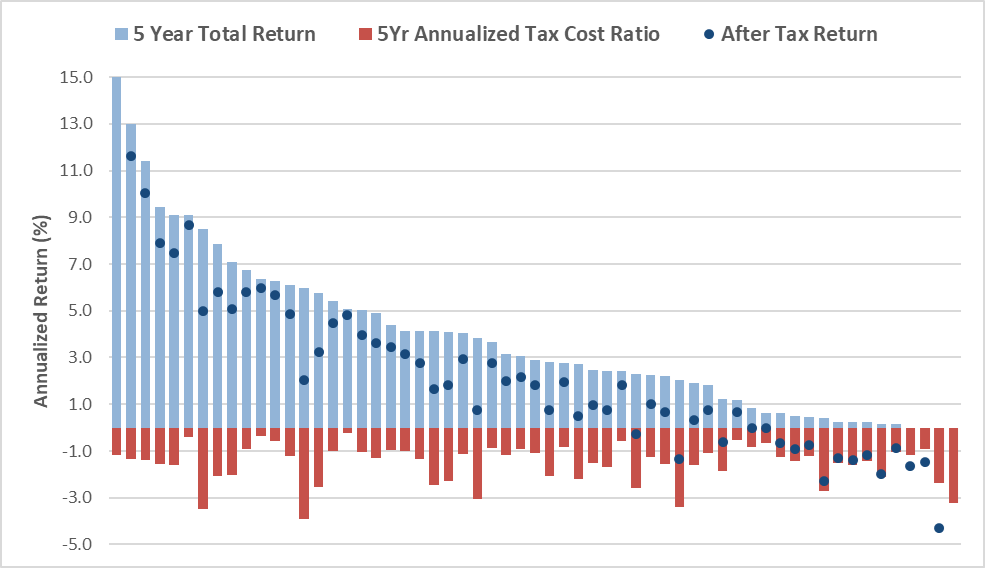

Fortunately, Morningstar has a handy metric that shows the after-tax returns of funds assuming the top bracket for ordinary income and capital gains called the Tax Cost Ratio. It’s essentially a measure of the unavoidable, uncontrollable drag from taxes in retail funds. A friend of mine made me aware of the metric and shot over a subset of funds with Morningstar Tax Cost Ratio data. Take a look at the results below. Each bar is a fund. The light blue is the headline total return, the sort of thing you’d see posted on the fund’s website. The dark red deduction is the tax cost in the highest bracket. The dark blue dot is the net after-tax return. Everything is calculated over 5 years and annualized because, as you can imagine, there is quite a bit of variability from year to year depending on fund turnover and distributions.

There are a few key observations. First, tax cost is not trivial. The average annualized tax cost for these 59 funds is 1.54%. For taxpayers in the top brackets, that is a real annualized reduction in return that either needs to be paid out of pocket, with the fund distribution or through fund liquidations. Second, some funds are better than others when it comes to tax cost. A Credit Suisse Commodities Trust rings in as the least tax-efficient fund with a 5 year annualized tax cost of nearly 4%. Fidelity Advisor Capital Appreciation holds up the other end of the spectrum with a 5 year annualized tax cost of just 22bps.

Third, some fund types seem to be more tax efficient than others. Traditional large-cap equities and fixed income seem to have less tax drag than real estate, commodities, small-cap and tech. But there are certainly category busters. The second worst fund in terms of tax drag has the same headline category (Capital Appreciation) as the best fund for tax drag. A basic materials commodities fund is one of the lower funds and another commodities fund is one of the highest. Vanguard’s real estate index is just below average for tax drag, Virtus Duff & Phelps is one of the worst. It’s hard to paint with a broad brush.

It’s important to note that tax cost is a reflection of the annualized drag on returns from taxes that are out of the investor’s control, not a metric that shows the total tax burden of buying, owning and selling the fund. Annualized tax cost is essentially added to basis for the purposes of calculating the final gain insofar as assets are sold and repurchased with a new basis. You don’t pay tax on the same gains twice. Distributions are obviously always taxed separately from capital gains at sale. But the big story isn’t so much total tax burden. It’s tax geography. It’s the fact that owning these funds requires relinquishing some degree of tax control.

Putting these funds inside of a life insurance policy pushes the tax incidence up from the fund and to the product. In other words, there is no uncontrollable, unavoidable “tax cost” of owning these funds inside of a life insurance policy. At worst, the client can control ultimate tax incidence by withdrawing or surrendering and paying ordinary income on gains in excess of basis, which mean that the client had the benefit of tax deferral along the way. Whether that deal makes financial sense for a particular client depends on their tax bracket and the tax nature of the returns coming from the fund. If it’s ordinary income anyway, then life insurance tax treatment is a wash. If it’s capital gains, then life insurance gains treated as ordinary income may actually make using life insurance less efficient than owning the fund outright.

But, of course, policyholders also have the ability to take loans instead of withdrawals and therefore avoid tax on gains altogether. That makes the math a heck of a lot easier. For simplicity’s sake, we can assume a wash loan provision. That’s the most efficient way to get money out of a Variable UL policy. From there, the question is pretty straightforward – are life insurance policy charges worth avoiding tax drag?

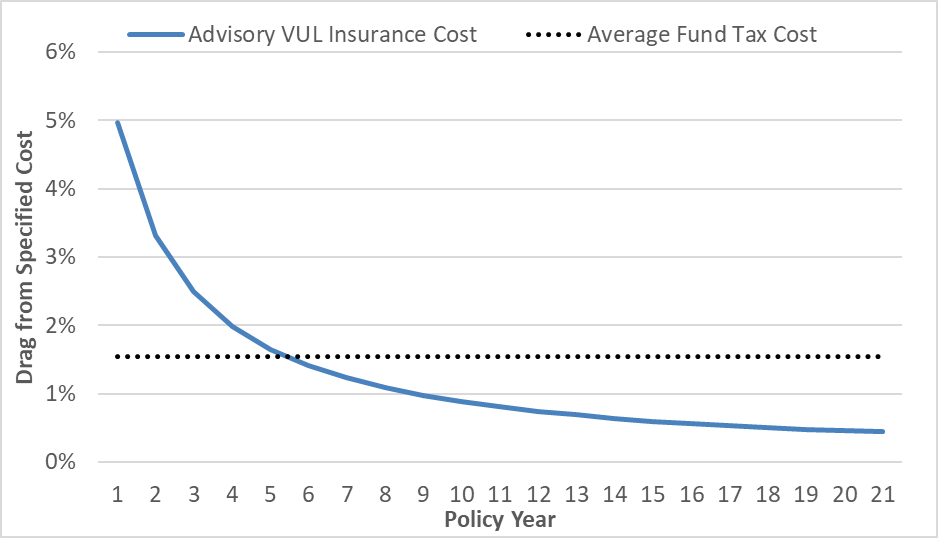

The cleanest point of comparison is Nationwide Advisory VUL, which doesn’t have traditional heaped compensation, surrender charges or premium loads in excess of the applicable state premium tax. Take a look at the drag from policy charges relative to the annualized tax drag, not including any additional taxes upon realization:

With this product, it takes a scant 6 years for the insurance to be cheaper – much cheaper – than the tax cost of owning the funds outside of life insurance. The higher cost in early years for Advisory VUL is related to three things. First, there is a state premium tax of 1.4% used for this example, which is on the low side. The average is closer to 2%. Second, the funds in Advisory VUL are slightly more expensive than their retail counterparts, tacking on around 10bps (on average). Low-cost funds that clearly don’t have revenue sharing agreements with Nationwide have additional fees of either 0.2% or 0.35% tacked on top.

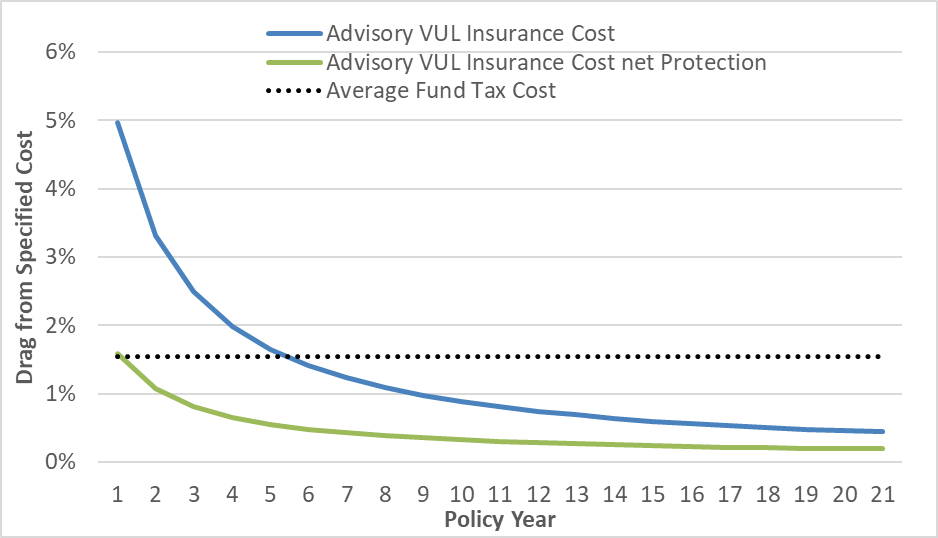

But the biggest line item expenditure for Advisory VUL is the cost of protection, which is Advisory VUL’s terminology for its initial flat, Term-like cost of insurance charge. I think it’s fair to argue that those expenses should not be included for the purposes of comparing owning life insurance to paying taxes. If the client has a death benefit need that would need to be covered anyway, then the protection cost is sunk cost. And even if the client didn’t necessarily need more death benefit, the actuarial value of the death benefit relative to the cost is (for the sake of argument) net neutral. Either way, the protection cost shouldn’t be included, as I’ve argued in previous articles. Here’s how the comparison looks after taking the cost of protection out:

Not surprisingly, life insurance holds the edge in terms of incurred costs – policy costs vs. tax costs – almost right out of the gate after removing the cost of protection. The average tax cost modeled here is 1.5%. The premium load is 1.4% plus an average of an additional 0.1% in fund expenses, plus a handful of funds with the additional expenses for being low-cost. Therefore, the two are neck-and-neck after the first year.

But in year 2, only the new premium incurs the load and the net insurance cost drops as a percentage of assets and continues to decline all the way down to just 0.2% by year 20. Not a single fund in the Advisory VUL lineup has a retail fund counterpart with an annual tax cost of less than 0.2%. Not one. Choosing Advisory VUL over a taxable portfolio should be a slam dunk – especially given that the product allows for advisors to charge fees based on assets just like a normal wrapped advisory account. In the bout of tax drag vs. Advisory VUL, it’s a knockout.

The math is trickier for retail VUL products. For those, the cost of protection isn’t the biggest line item, at least not initially. Instead, the biggest line item is per-thousand charges used to recapture commission. These charges push out the break-even period between life insurance and tax cost to 17 years even after deducting the protection charges. But I don’t think that’s necessarily the right comparison. A street VUL pays commissions, but there are no advisory fees baked into the fund costs. If we deduct a typical 1% fee from the fund return, the breakeven between a taxable fund and a retail life insurance policy drops to 13 years.

In the long-run, though, retail VUL with heaped commissions holds the edge over fee-based products like Nationwide Advisory VUL that are saddled with a typical 1% AUM fee. But that misses the point. Waiting 13 years just to break even on the tax side of the house is far enough out that for advisors and their clients who are fundamentally skeptical about life insurance, it’ll basically never happen. As a result, life insurance gets left out of the conversation.

There’s an old saying in sales – “if you’re explaining, you’re losing.” Pitching retail VUL requires no small bit of explaining, even if the ultimate performance is better. Fee-based products like Advisory VUL don’t. The benefits of the product start to accrue right out of the gate. There is no waiting period. Paired with a tool like Morningstar Tax Cost Ratio as a direct comparison of the tax cost of owning the fund in a brokerage account or a life insurance policy should make these conversations very simple and very straightforward.

And isn’t that the point? To use another well-trod saying, “life insurance is sold, not bought.” That’s true for retail VUL, even though the ultimate advantage in terms of economics are arguably better. But with a comparison point as compelling as the Morningstar Tax Cost Ratio, I’d argue that fee-based VUL should be bought, not sold, in a way that retail VUL can’t.

1/18/2024 Update – A carrier subscriber shot me a note making two points. First, Vanguard actually shows this information for its funds as well, including the taxable return assuming full share disposal. For VTSAX, for example, 10 year returns before taxes were 11.43%, including taxes on distributions drops it to 10.95% (which makes sense given that it’s a passive benchmark fund) and to 9.35% after including taxes upon sale of fund shares. Second, he brought up the fact that most financial plans involve periodic portfolio rebalancing, which itself will potentially force tax incidence – but not in a life insurance policy.