#408 | Reliastar Raises Base Charges

8/27/24 Update – I just received an email from a subscriber about another Reliastar policy with charge increases, this time affecting both the base charges as described below in this policy and the premium load, which jumped from 0% to 10%.

A couple of weeks ago, a subscriber to TLPR forwarded a letter from Reliastar, the Voya entity that used to write a substantial portion of its Life business, announcing an increase to the “Monthly Charge per Thousand of Specified Amount.” The impact on the policy isn’t ambiguously described in the letter, which states that “the increase in this monthly charge will reduce the Accumulated Value of the policy and may impact the length of time the policy will provide death benefit coverage based on current premiums.” One of the options presented in the letter, beyond doing nothing or paying additional premiums, was to surrender the contract. Pretty bleak.

At first blush, this looks like yet another increase to Cost of Insurance rates – referred to simply as the “Monthly Charge per Thousand” but it’s not. Cost of Insurance charges are deducted monthly, but they’re denominated based on Net Amount at Risk, which is the difference between the current Death Benefit and the Account Value. The charge referenced in the letter is based on the “Specified Amount.” In most contexts, the Specified Amount is the initial policy Death Benefit. The actual Death Benefit can be the Specified Amount or more, in the case of an overfunded policy that has hit a tax corridor, or less if there are outstanding policy loans.

So what is this “Monthly Charge per Thousand of Specified Amount?” It’s the charge with a thousand names – base charge, per $1k charge, unit load, administrative charge and a smattering of others, depending on the life insurer. For the purposes of this article, we’re going to refer to it as a base charge. The primary purpose of the base charge, as described explicitly in some contract forms, is to recapture the costs of distributing the product and to provide a return on carrier capital. The base charge, in short, exists because of heaped commissions.

Whole Life handles commission recapture with a massive front-end premium load. That’s why paying $100,000 into an all-base Pay to 100 Whole Life policy results in very little cash value in the first couple of years. The carrier is essentially matching their commission payouts – in addition to required capital and other expenses – with the front-end policy load. Matching is the most efficient way to finance commissions because it doesn’t require the policyholder to essentially “borrow” money from the insurer to pay the agent.

There is no functional reason why Universal Life policies couldn’t replicate the Whole Life front-end load structure, but they don’t. My sense is that part of the reason is that Universal Life policies are transparent and it would be hard to sit down with a client and explain why there is a premium charge equal to their first year premium without talking about commissions, which many agents are loathe to do. As a result, Universal Life policies amortize the cost of the commissions through the base charge over (usually) the first 10 years of the policy. The client essentially borrows money from the insurer to pay the commissions and is charged interest at the carrier’s cost of capital, which is usually north of 12%. Over 10 years, that tallies up to around $1.7 for every dollar of commission paid. That’s less than ideal for policyholders*.

But if that’s what base charges are for, then why is Reliastar raising the base charge on a policy from 1998? The surrender charge burned off years ago and so did the initial base charges that were designed to recapture the commissions. The answer, obviously, is that the base charge increase has nothing to do with commissions and everything to do with product economics. The policy in question is Survivorship Estate Design and it sports a minimum guaranteed crediting rate of 4.5%. We’ve seen companies in the past try to blunt the damage of high guaranteed crediting rates by using increases to Cost of Insurance rates. But here, it looks like Reliastar is instead relying on increasing the base charge to get the job done.

This raises a bigger question – how, how high and for how long can a life insurer increase a policy charge that most policyholders don’t even know exists?

To answer the first question, I pulled Universal Life contracts approved from 2003 to 2023 from 28 life insurers to find and extract the language around non-guaranteed element changes and, specifically, changes to the non-guaranteed base charge. Some common elements became immediately apparent. Virtually every company has contract language specifying that non-guaranteed elements can be changed at the “sole discretion” of the life insurer “based on [the] future expectations” of a host of factors including investment earnings, mortality, persistency, expense experience, taxes and reinsurance costs, among other things.

The goal of this sort of contract language is to be specifically ambiguous about the conditions that would lead to changes to non-guaranteed elements. Specific in that the carrier provides a list of potential drivers of a change to a non-guaranteed element, but ambiguous in that the list is comprehensive enough to provide air cover for any change the life insurer wants to make. And, on top of that, the lists almost always talk about future expectations, not actual experience. What are expectations? Whatever the carrier thinks are justified, whether they come to pass or not. This language doesn’t exist to protect consumers. It’s there to protect life insurers when they want to make a change.

Consider the difference between Lincoln’s NGE language in 2015 relative to the language in one of its 2021 contracts. Take a look, with emphasis added and some language regarding Redetermination Classes removed for clarity:

| Lincoln 2015 | Lincoln 2021 |

| We will base any change [to non-guaranteed elements] on Our future expectations as to investment earnings, mortality, persistency, expenses and taxes.” The 2021 version reads a little bit differently. | We have no obligation to adjust the NGEs although in our discretion we may choose to do so. Such changes can be made in consideration of one or more future anticipated or emerging experience factors which may include, but are not limited to: mortality, interest rates, investment earnings, general market conditions, persistency, expenses (including reinsurance costs and taxes), policy funding, Net Amount at Risk, loan utilization, capital requirements, and reserve requirements. |

The 2021 version is substantially more protective of Lincoln than the 2015 version. I’ve written in the past about COI lawsuits where the life insurer failed to lower COIs even though their overall mortality has improved. Presumably to head off that risk, Lincoln states that they have no obligation to adjust NGEs. Some of the COI increases we’ve seen over the past decade have been related to policy funding, including the COI increases at PHL Variable, so Lincoln inserted both “policy funding” and “Net Amount at Risk” into the language. There is also now cover for events out of the company’s control relating to “general market conditions,” “capital requirements” and “reserve requirements.” Basically, anything goes. And it’s not just Lincoln. Contracts from Prudential (2020) and Allianz (2017) have nearly identical lists.

Other companies actually go even a step further by including profit – yes, for real, profit – as a justification for changes to non-guaranteed elements. F&G, Securian, Nationwide, Principal, Prudential and PacLife all specifically list profit under one of the factors. PacLife says specifically that “We may profit from such charges.” Including profit into the mix allows life insurers to change NGEs not just in the event that they’re losing money, but also in the event that they’re not making as money as they thought they would – and the reason for that could be literally anything. Profit operates as a catch-all, but it’s more than that. What about a company that gets purchased by new owners and suddenly has new profit hurdles to hit? Does that mean an insurer could change NGEs just to make more money with no justification?

In every contract that I reviewed, this sort of language is always, without exception, applied to Cost of Insurance rates. That makes sense. Cost of Insurance is a technical term that is referenced in regulatory documents, including standardized mortality tables. If you look through the Interstate Compact standards for Universal Life policies, the only named policy charge in the entire document is “cost of insurance.” Everything else is simply referred to as “expenses,” “expense charges” or “other charges.” It would be extremely hard to for carriers to make changes willy-nilly to Cost of Insurance rates without justification because the implication is that Cost of Insurance is mortality. Hence, the expanded language in the contracts to clarify that Cost of Insurance rates are determined on the basis of many things, including but not limited to mortality. It’s air-cover.

A little less than half of the contracts that I reviewed also extend the same language to all non-guaranteed charges, including Reliastar. Why, then, did Reliastar choose to increase the base charge rather than the COI charge? My hunch is that it has to do with litigation. Everyone knows that changing Cost of Insurance rates is a third-rail. If you change COI rates, you will get sued and you will lose. There is no precedent for changing base charges. To my knowledge, there have been no lawsuits on base charges. I don’t even know if any company has changed base charges in the past. It flies under the radar.

A quarter of the contracts actually extend the language on non-guaranteed elements beyond charges and also to non-guaranteed crediting rates, interest bonuses and, in the case of Indexed UL, participation parameters such as Caps and Participation Rates. This is very clever. By applying the same language to all NGEs, including interest crediting, the carrier can make the argument that they make changes to NGEs all the time at their sole discretion for all sorts of reasons and no one sues them or asks for specific justification. Routinely changing a Cap or crediting rate is, for the purposes of the language, the same thing as changing a base charge. They’re both fully covered.

The final quarter of contracts take a markedly different approach. All of them have comprehensive NGE language and factors for changing COI rates, but they treat base charges and other policy expenses differently. Take a look at the carriers and their language:

| Carrier | Accordia | ANICO | Americo & Guardian | Columbus Life | Symetra | Transamerica |

| Base charge Language | “The Monthly Expense Charge is determined by Us” | “We reserve the right to reduce or increase the Monthly Expense Charge” | Simply states that the guaranteed maximum is shown in the data page | “At Our option, We may charge less than the maximum rates shown.” | “The Company may charge less than the maximum charge” | “We determine the Per Unit Charge Rate and may change it from time to time…” |

These companies have purposely extracted base charges (and other policy expenses) from the factor-based language for changing NGEs. Why? Because base charges are non-guaranteed elements without a universal definition. The industry doesn’t even have a consistently used nomenclature for them. And like any non-guaranteed element that is unique to a particular policy, the reality is that the life insurer should be able to change it however they see fit, whenever they see fit. And that’s that.

Or is it? The real question isn’t why life insurers may change base charges. The real question is why life insurers choose to make base charges a non-guaranteed element. Unlike Cost of Insurance rates, base charges and other policy expenses don’t factor directly into tax testing for life insurance policies*. Guaranteeing Cost of Insurance rates at current levels would have a direct and negative impact on MEC, Guideline and CVAT limitations. Carriers offer non-guaranteed Cost of Insurance rates even if they have no intention, ever, of changing COI rates because of the tax implications. The same can’t be said for base charges. There is no tax or reserving reason to not guarantee base charges. If base charges only exist to recover commissions, which is a pretty simple and straightforward calculation, then why do carriers leave them as a non-guaranteed element?

Partly, I think, out of habit. At MetLife, we released a product and started to get feedback that the guaranteed side of the ledger looked terrible. I happened to be at lunch with our head of pricing for life insurance one day and asked him about it. I’d assumed that the per thousand charges had something to do with tax testing. He told me they didn’t and I asked him why we set them so high. His response floored me – “I don’t know. We just pulled over the guaranteed charges from our last UL chassis.” The previous product was a Guaranteed UL designed to strip as much cash value from the policy as possible. The new product was designed for accumulation. It was a massive misstep that we quickly remedied with an endorsement to reduce the guaranteed charges to more reasonable levels.

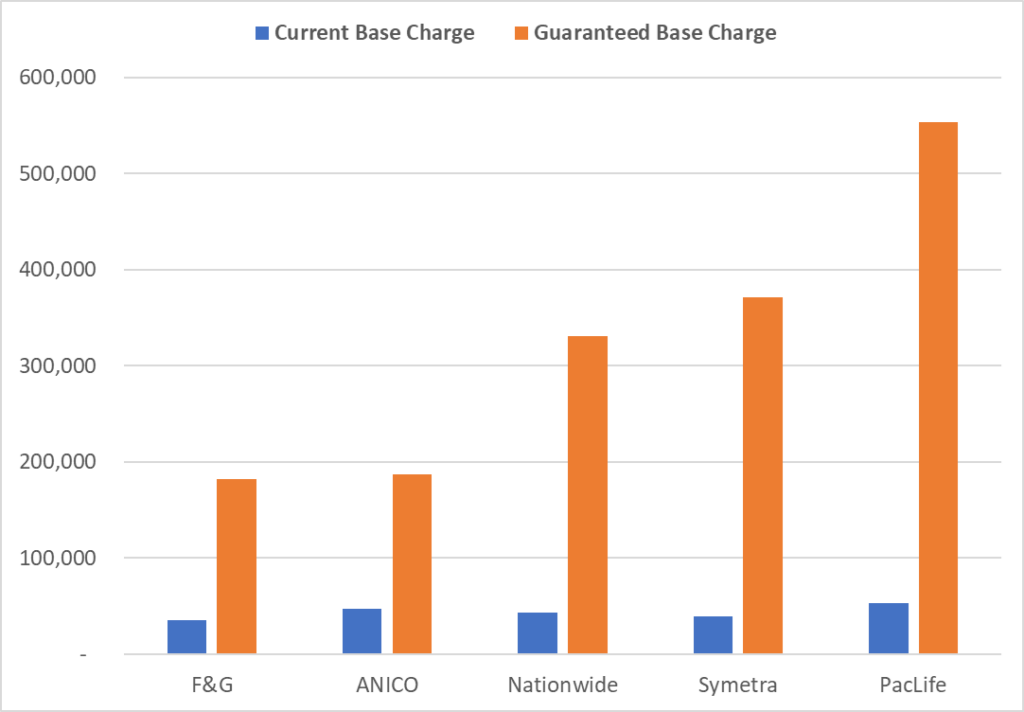

We pulled a sample of products just to see how the current base charges compare to the guarantees on a particular cell. We only tallied the first 40 years of the policy, which is about Life Expectancy on this cell, in order to keep the graph easy to read. The difference between currents and guarantees is, shall we say, notable. Take a look.

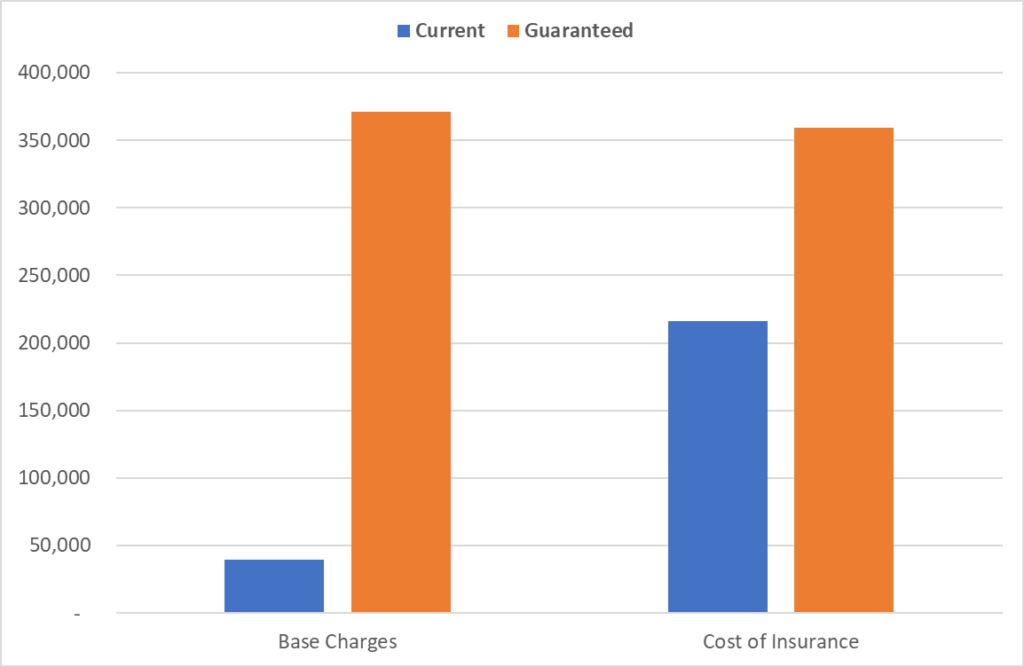

The ratio of guaranteed to current charges ranges from 5.2 times at F&G to a whopping 10.5 times at PacLife. Everyone knows that the guaranteed side of any Universal Life illustration looks terrible, but my sense is that most people blame the COIs. The real issue is actually the guaranteed base charges. Take a look at the change between current and guaranteed rates for Symetra over the first 40 policy years:

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that for policyholders with policies that are less than 30 years old – the vast majority of policyholders – the negative impact of a change to guaranteed base charges is much greater than a change to guaranteed Cost of Insurance rates. And yet no one talks about it. Carriers do a disgracefully and infuriatingly poor job of disclosing base charges on illustrations. The reason there aren’t more carriers being shown on these graphs is because so few actually provide any disclosure of guaranteed base charge rates. Some of them barely even describe the fact that the policy has base charges despite the fact that base charges constitute the single largest expense line item in the first 10 years of the life of a policy.

There are, however, some companies that have taken a notably different approach. OneAmerica’s Variable UL product guarantees all policy charges in all years. Everly Life has filed an Indexed UL product that also has guaranteed base charges for a period of time. John Hancock has fully guaranteed base charges in its policies. The fact that some companies are offering guaranteed base charges is proof that it can be done – and that every company should do it.

What happens after the base charge increase at Reliastar could have ripple effects across the industry. One of the great fears in the insurance industry is that institutional-backed or privately-held financial holding companies will buy up blocks of business and mess around with non-guaranteed elements. Reliastar reinsures all of its life business to Security Life of Denver, which is wholly owned by Resolution Life. The decision to increase base charges undoubtedly came from Resolution. If they can do it without getting sued, then it may signal to other companies that it’s open season on non-COI non-guaranteed elements. Behind the weak dam of industry decorum and contractual language lies a vast lake of profits, just waiting to burst out – regardless of who gets drowned.

*As discussed in a previous article, policy expense do factor into the Necessary Premium Test, but they play merely a supporting role.