#369 | Brighthouse SmartGuard Plus

Quick Take

There is no doubt that Brighthouse SmartGuard Plus is one of the most innovative new products to hit the market in a long time, blending the competitive guaranteed income of an annuity with the income tax advantages of a life insurance policy, all under a rapid-issue underwriting process that will appeal to annuity writers. It’s the holy grail for insurance products. There’s just one little problem. In order to make it work, Brighthouse went all-in on the Guaranteed Distribution Rider, which is automatically included in all policies and comes with a fee, that requires taking a particular interpretation of tax law theoretically allowing for products like this to exist but has never actually been tested with the IRS. Other companies such as AIG and National Life have used similar constructs in optional riders but stopped well short of where Brighthouse went with SmartGuard Plus. From my vantage point, although the product and economics are compelling, the tax risk in SmartGuard Plus is real and should be seriously considered by customers, distributors and potential competitors.

Full Article

At first blush, the defining characteristic of Brighthouse’s new SmartGuard Plus – yes, Brighthouse is apparently still in the life insurance business – is that it is has buffered indexed crediting strategies. With SmartGuard Plus, Brighthouse follows Prudential and Equitable into the growing category of registered index-linked life insurance products. All three companies have had incredible success with buffered strategies in annuities and it makes sense that they’d take those same concepts and apply them to life insurance.

However, each company has taken a markedly different approach to the actual application of the concept. Equitable put the buffered strategies in the MSO II rider that can be added to all 5 of their VUL products, each one built for a different sales application ranging from protection to accumulation to early cash value to simplified underwriting. Prudential put the buffered strategies in a specific product, FlexGuard IVUL, that can be used either for its low-cost secondary guarantee or for accumulation. And Brighthouse? Well, they decided to do something different with SmartGuard Plus. Really different.

The best way to think of SmartGuard Plus is that it is essentially a two-phase product. In the first phase, the product looks like any other accumulation-oriented life insurance product. Out of the box, it’s designed to be funded over 10 years all the way up to the MEC limit with a level death benefit. CVAT is the only available 7702 test. After annual policy charges are deducted, the remaining account value is eligible to receive either a positive or a negative index-linked credit, depending on the calculated index performance adjusted by the applicable buffer and cap. Standard stuff for a simplified accumulation design with the twist of having buffered indexed credits.

Phase two starts when the policyholder triggers the Guaranteed Distribution Rider (GDR), which is automatically included on all policies, comes with a substantial charge and is, in my view, the defining feature of the product. SmartGuard Plus doesn’t really work without the GDR. Once the GDR is triggered, which can happen any time after the 10th year, the account value is immediately allocated from the indexed strategies to the fixed account and the policy essentially converts into an annuity. The policy begins to pay guaranteed income as net zero cost (wash) policy loans. The guaranteed income is determined by the GDR Guaranteed Distribution Payment Rate multiplied by the account value. And here’s the key – the income amount is guaranteed for the life of the policyholder even if the net cash value runs all the way to zero.

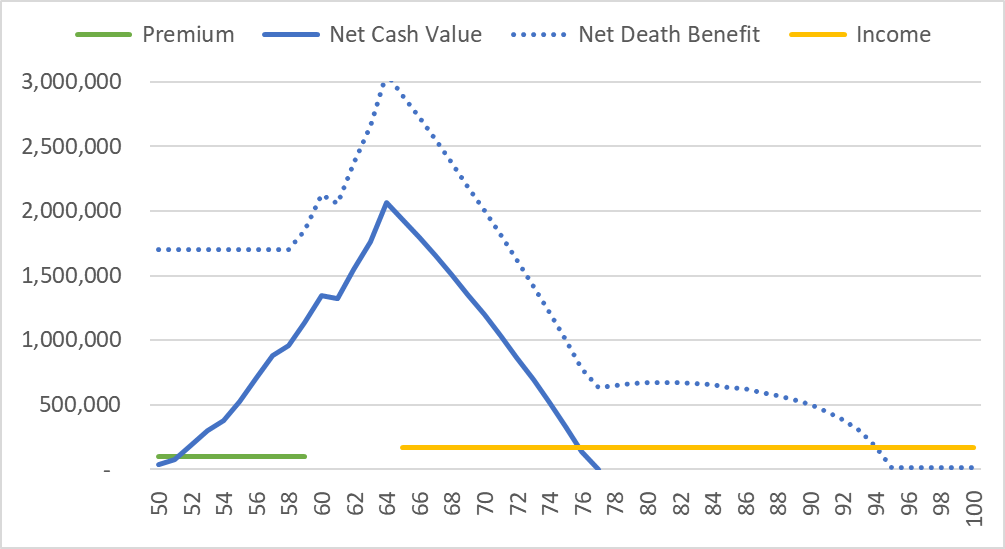

Let’s use a real illustration and example on a male, age 50, nonsmoker rate class (Preferred not available due to rapid-issue fluidless underwriting). We assume a $100,000 annual premium for 10 years. Assuming historical S&P 500 returns from 2007 through 2022 and the 10% Buffer strategy with a 19% currently declared Cap, the account value at the end of the 15th year is $2,065,915. The Age 65 GDR Guaranteed Distribution Payment Rate for this client is 8.02%. Multiplying 8.02% by $2,065,915 yields a guaranteed income amount of $165,773. Based on the current fixed account crediting rate of 3.25% and annual income of $165,773, the net cash value drops to zero in just 12 years at age 77.

At that point, the magic of the GDR begins to show. A little asterisk shows up on the cash value column with an explanation at the bottom of the page that says “Cash Value is increased to cover the Distribution Payment.” In other words, the GDR splashes a bonus into the fixed account concurrent with the new policy loan to cover the distribution payment. The fact that the GDR steps in with a bonus to cover the distribution payment allows the policy to remain in-force and carrying whatever net death benefit is left over until age 95, when it drops to the $10,000 guaranteed minimum. Here’s what the illustration looks like graphically:

This is a very clever structure. Exceedingly clever. Why? Because the structure theoretically allows for the guaranteed lifetime income to be, like any other policy loan, income tax free. Brighthouse spells it out clear as day in the illustration: “Distribution Payments under the Guaranteed Distribution Rider (GDR) are made in the form of Policy loans. A policy loan is generally not treated as a taxable distribution if the Policy is not a MEC and the Policy remains in force during the lifetime of the Insured. As a result, the Company generally does not intend to report the benefits payable under the GDR to the IRS as taxable income based on the Company’s current understanding of the applicable tax law.” Although, to be clear, “you should consult with your qualified tax advisor to determine the tax consequences of the GDR and the Policy.” I’m sure policyholders will get right on that.

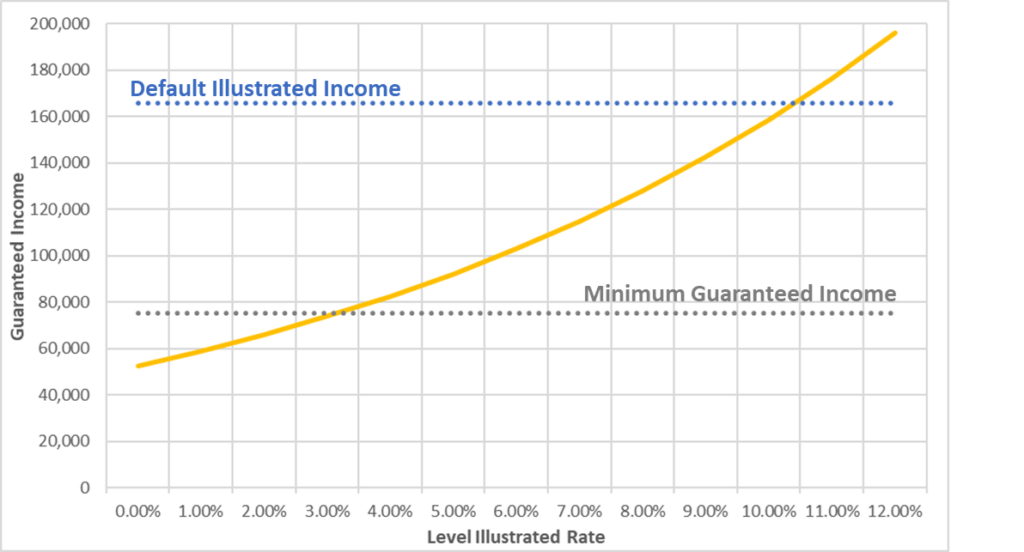

It is very clever, but is it competitive? That depends on how you look at it. Because of the two-phase nature of the product, the assumption you make about the performance in the first phase using the buffered crediting strategies has a direct impact on amount of guaranteed income in the second phase using the GDR. The minimum income is a dollar amount specified in each individual contract. For the illustration I have, the guaranteed minimum income is $75,308 from attained age 65 until death, which is the equivalent to using the 8.03% withdrawal rate on an account value of $937,833 in the 15th year.

Compared to a Deferred Income Annuity with a single premium of $811,090 ($100,000 for 10 years discounted back at 4%) for a 50 year old starting income at age 65, just like the SmartGuard Plus scenario, the guaranteed income is $135,000. Even with an exclusion ratio for taxation, $135,000 out of a DIA is far higher than the guarantee in Smart Guard Plus. Even taking the cost of term coverage into consideration, the DIA produces better guaranteed income by a country mile. Fixed Index Annuities with income riders also show better guaranteed income. No matter what way you cut it, the sale for SmartGuard Plus is not the base guaranteed income amount.

Instead, the appeal for SmartGuard Plus is the ability to lock in guaranteed income based on a growing account value over time. This is not a unique value proposition. Some of the most popular annuities in the market use the same growth-driven income structure, including Brighthouse’s own Shield Level Pay Plus annuity. The difference between SmartGuard Plus and Shield Level Pay Plus, though, is that like any life insurance policy, SmartGuard Plus has explicit policy charges that drag on the growth of the policy. But it also has additional charges related specifically to the Guaranteed Distribution Rider and they’re not cheap. Over the first 15 years of the policy, total charges on my illustration tallied up to a little over $330,000. By comparison, an identically configured Lincoln AssetEdge VUL has just $190,744 in charges over the same period.

The first order of business for SmartGuard, then, is to produce performance high enough to overcome the substantial charges so that the account value exceeds $937,833, which is the account value equivalent to produce the guaranteed income stream of $75,308 (8.02% * $937,833). For every dollar above that value, the guaranteed income level will increase. The illustration I received, for example, has a guaranteed income of $165,773 based on the illustrated account value in the 15th year. So what kind of illustrated performance do you need to get income that high? Take a look.

In order for the product to beat the guaranteed minimum, the performance has to be over 3.75%. The default level-equivalent illustrated rate for this cell, using historical S&P 500 returns from 2007 to 2022*, the 10% Buffer selection and the current 19% Cap, was a whopping 10.67%. That is steep. But it has to be. SmartGuard Plus has to dig out of a pretty big hole in order to just beat the baseline guarantee. From my vantage point, that dynamic basically excludes policyholders from using the fixed account or 100% Buffer (as in, 0% Floor) indexed account, which has a currently declared Cap on the S&P 500 of just 7%. That’s not enough to create any real potential for future growth that will exceed the guaranteed minimum. At that point, the client would be much better off in a traditional Fixed Index Annuity. SmartGuard Plus works well – and arguably only works well – when the client is willing to swing for the fences on risk and assumed reward.

The proper point of comparison, then, is a Variable UL with a heavy equity allocation. It’s a bit of a tricky comparison though because there is really no other product like SmartGuard Plus. If you run a traditional VUL with income for life, it has to carry quite a bit of residual cash value and death benefit along the way, so the comparison isn’t clean because SmartGuard Plus exhausts its cash value with income and holds very little death benefit while it relies on credits from the GDR. A better comparison is to run a VUL with income to 95, which leaves less residual account value and death benefit but enough to equal 5 years or so of remainder income.

Running Lincoln AssetEdge VUL under this scenario using a 10.67% net return, illustrated income is a little over $250,000, handedly outperforming SmartGuard Plus out of the gate by every metric. In other words, if the client is swinging for the fences, then the additional costs embedded into SmartGuard Plus to provide the income guarantee aren’t worth it. Instead, SmartGuard Plus takes a more nuanced view that, I think, is more representative of how people actually think about VUL. During the accumulation phase, maybe a 10.67% illustrated return is defensible, but certainly not during distributions. Therefore, using a 10.67% return forever for an income illustration is pretty unrealistic.

The real question is what illustrated rate after the 15 year accumulation period cause AssetEdge VUL to produce identical income in years 16+ to SmartGuard Plus. The answer, for this cell at least, is a 5.75% net assumed rate. In other words, that’s the return hurdle that a client would have to beat in order to generate better performance out of AssetEdge VUL. Anything below that and SmartGuard Plus’ guarantee is providing value. I think that’s a pretty strong story for consumers. A 5.75% long-term equity assumption is conservative, to be sure, but it’s not unrealistic. Some major research firms are projecting decades of sub-5% returns for US equities. From my vantage point, the guarantee in SmartGuard Plus delivers real value.

If Brighthouse is going to sell this thing, then it better. Unlike AssetEdge VUL, there is no other ancillary use for SmartGuard Plus. It can’t do protection. It isn’t built for non-guaranteed income without the rider. It is a single-use instrument designed for tax-free guaranteed income courtesy of the GDR. End of story. This singular focus makes SmartGuard Plus the first of its kind. It’s a life insurance policy designed and sold explicitly for guaranteed income, which is the domain reserved for annuities.

According to Brighthouse’s interpretation of insurance tax law, this product is the holy grail – guaranteed income like an annuity, tax treatment like a life insurance policy. It’s the best of both worlds. When you combine those features with Brighthouse’s rapid issue underwriting process that will appeal to annuity sellers, it has the potential to carve out a whole new product category. Every company with both a life insurance and an annuity operation will immediately see the power of it and will build their own version. There are billions of dollars in annuity flow that could be diverted to this sort of product. It very well could be the next big thing in the insurance industry.

There’s just one problem – Brighthouse is not the first company to dream up this idea. National Life was the first in 2014 with its Lifetime Income Benefit Rider and AIG followed with Income For Life in 2016. Both of those riders operate under the same basic concept as the GDR. They allow for a guaranteed income stream for life and if the net account value drops to zero, then the rider kicks a bonus into the account value to cover distributions. And like Brighthouse, both National Life and AIG automatically include the rider at policy issue. Brighthouse obviously relied on the groundwork laid by AIG and National Life in creating the GDR.

However, there are some substantial differences between how National Life and particularly AIG approached the product design versus Brighthouse. National Life and AIG do not charge a fee for the rider until exercise. For National Life and AIG, their guaranteed income riders are ancillary features that can be triggered later at guaranteed payout rates for National Life and currently available payout rates for AIG.

The payout rates are also substantially lower than in SmartGuard Plus. AIG’s look to be around 5% for a 65 year old and National Life’s are in the 6% range based on the 2014 filing. Brighthouse, by contrast, has payout rates of over 8% for the same cell and deferral. The chance of AIG and National Life’s policies exhausting their cash values and relying on the bonus payments to keep the policy in force is much lower than in SmartGuard Plus. For AIG and National Life, the actual incidence of a policy relying on bonus payments to maintain guaranteed income is somewhat theoretical. For Brighthouse, it’s a virtual certainty given that the product is designed exclusively for that purpose.

This leads to the other big difference between how National Life and AIG approached their riders versus Brighthouse. Both companies require that the policyholder use Guideline Premium Test. There is a very logical reason for that. The required corridor between the cash value and the death benefit is prescribed in Section 7702. The Cash Value Accumulation Test, by contrast, uses a calculated corridor based on guaranteed credits and Cost of Insurance. The calculated corridor is then hard-coded into the policy contract.

If a company is providing guaranteed credits to the policy in order to maintain guaranteed income, which is absolutely going to happen under the Brighthouse design**, then I would argue – and, to be clear, it’s not just me because this design has been dreamt up by quite a few people – that those guaranteed credits need to be brought into the CVAT calculation. The problem is that the guaranteed credits are not known because there are non-guaranteed elements that will determine the future guaranteed credits paid into the contract. As a result, CVAT arguably shouldn’t even be available because it’s impossible to set the contractual table appropriately.

Let’s assume that Brighthouse got around that problem by setting some worst-case scenario for guaranteed credits. That is logical. If that was the case, then we would expect that the policy has to carry significantly more death benefit in order to account for the future guaranteed credits. But that’s not the case. The SmartGuard CVAT corridor factors are spot-on with other carriers, if not a little bit aggressive because of the age 95 terminal rate. I think there are going to be a lot of tax actuaries at life insurers who are scratching their heads over how Brighthouse is looking at Section 7702 compliance with this product.

From my vantage point, the tax complexity of the product is problematic. National Life’s filing more or less doesn’t talk about tax treatment, essentially leaving it up to the client to interpret, but AIG is explicit about it. In bold, at the top of the page, is the following text: “Benefits paid under this rider may be taxable. If so, You may incur a tax obligation. You should consult Your personal tax advisor to assess the impact of this benefit.” Brighthouse, by contrast, merely makes a nod in the illustration to the fact that “tax law is complex and subject to change,” followed by some language about Brighthouse reserving the right to change how it reports taxation in the future.

In my view, this language should be thoughtfully considered and not ignored as a typical over-reaching, all-encompassing corporate CYA clause. There is real tax risk at play. Overloan Protection Riders have still not been opined on by the IRS. There is a feeling that I’ve heard articulated by several tax lawyers that there is no way OPRs will fly and companies that have relied on them will likely have some serious tax remediation issues. The riders used by National Life and AIG are essentially mega-OPR designs. They carry the same sort of caveat emptor as OPR for the likely small subset of policyholders who ultimately elect to use them.

But the tax issue is much more foundational for SmartGuard Plus. The only reason to buy the product is for the Guaranteed Distribution Rider. Every single sale is reliant on it. Every single customer who uses the product as intended will exercise it. Because the implications of the GDR reach all the way back into the contractual death benefit corridors, it’s not entirely clear what the tax consequences of the IRS taking a different view than Brighthouse would be, but the risk should absolutely not be ignored.

Choosing SmartGuard Plus fundamentally requires taking on tax risk in a way that is different from anything else on the market. That alone should be reason to pause and seriously consider the potential consequences of the tax risk, especially for the large institutional firms that Brighthouse is courting, even considering the very compelling economics and value proposition of the product.

Illustrations are pretty hard to get, so for those interested, click here

7/31 Update – Over the weekend, I got received a note from a subscriber with an interesting take on the situation with this product. Here’s what it said: “I do really love the concept but…unless [Brighthouse] gets a patent like Lincoln did with the i4Life rider and obtains a PLR for the huge tax risk aspects here…all those eligible to sell this should take a pass. Just say no. Why? All reps are under a best interest standard, at least…this is a registered life product so caveat emptor fixed-life-only agents can’t sell this. This means only those exposed to Reg BI can sell it (those in NY have a higher standard, NY 187). If they are also a CFP, they are viewed by the CFP Board as a fiduciary in all things they do or don’t do. Thus, I see no way that anyone who can sell this, should sell this!”

*The default for the illustration is to show index returns starting in 2022 and working backwards for the length of the deferral period. The deferral in my illustration was 15 years so the time period was 2007 to 2022. However, you can pick different historical time periods to stress test the illustration.

**There are two situations where it won’t happen. First, the policyholder dies before the net cash value reaches zero. Second, if the fixed account crediting rate exceeds the guaranteed income payout rate. Both are exceedingly unlikely.