#257 | The Section 7702 Christmas Miracle

This is the closest thing to breaking news in our industry and, as such, it’s still very much evolving. Current updates to the post are at the very bottom.

For all of the buzz and lead-up to the creation and implementation of AG 49-A last year and its dramatic impacts on the Indexed UL market, my hunch is that AG 49-A is about to be forgotten, at least for a little while. Why is that? Because something even more transformative happened in the sleepy final hours of 2020. The change is going to be immensely positive, positioning life insurance to survive and even thrive in an ultra-low interest rate environment. It’s a Christmas miracle. But in the process, it’s going to completely upend the competitive landscape for accumulation products. As impossible as it may seem, 2021 could turn out to be an even more disruptive year for life insurance than 2020. Buckle up.

About a year ago, I was chatting with some friends at a major mutual company and they mentioned the idea of reforming Section 7702, the section of the Internal Revenue Code that defines life insurance for tax purposes. It seemed like a pretty far-fetched idea. Section 7702 hasn’t been materially changed in decades. Opening 7702 exposes the industry to potentially sweeping changes to tax treatment for life insurance. The old adage of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” seems like it applies to any attempt to bring Section 7702 back under the limelight.

But it was becoming obvious that Section 7702 was, in fact, broken. The tax limitations in 7702 are calculated by asking a simple question – at what premium level will the policy stay in-force based on specified charges and a specified interest crediting rate? The resulting value is what provides the basis for the CVAT corridor limitation and the GPT and MEC premium limitations, the latter of which is actually a subset of the CVAT calculation. The flaw in Section 7702 is that, almost inexplicably, the interest rate assumptions are hard-coded. For CVAT/MEC and the GPT Level Premium, the interest rate was hard-coded at 4%. For GPT Single Premium, it was hard-coded at 6%.

These interest rates are a very real and practical problem for companies selling Whole Life for a very simple reason – Whole Life policies must endow on a guaranteed basis, which is exactly the same calculation used to determine the tax limitations in Section 7702. Using any interest rate below 4% to create guaranteed cash values would have resulted in a violation of the 7702 limits after the premium payment period for the policy and for paid-up additions. Life insurers had no choice but to match their guaranteed interest rate to the Section 7702 rate – which creates a new set of problems because the valuation rate, which is used for setting policy reserves, is a floating rate. This creates a structural disconnect between the cash values and the reserves that only gets worse as rates continue to fall. But what’s a mutual company to do? Their hands were tied.

As I’ve written about in other articles, the 4% guaranteed minimum rate used by life insurers in Whole Life produces incredibly rich guaranteed values, particularly in short pay products. The solution of raising premiums only goes so far before the product triggers MEC status. Companies wanting to enter the growing short pay Whole Life market had a Devil’s bargain – sell a product that is primarily positioned for its non-guaranteed accumulation performance but at the cost of taking on guarantees that, by any metric, were too rich for the current economic environment. The further rates fall, though, the more the problem percolates out of short pay Whole Life and into all Whole Life varieties and paid-up additions. I don’t think it’s an understatement to say that the hard-coded rates in Section 7702 could have posed an existential threat to Whole Life availability in a prolonged ultra-low rate environment.

Until this year, that problem was more theoretical than practical. When the 10-year Treasury dropped below 1% in March, however, the problem became imminently practical. The mutual companies, in conjunction with the ACLI and Finseca, swept into action and successfully lobbied for a provision in the HEROES Act in May that would allow the interest rate in Section 7702 to float. The provision had an implementation date of 1/1/2021 and it allowed for a 2% rate to be used for the calendar year of 2021, after which the floating rate would take over. It was a soft, predictable landing for life insurers that allowed plenty of time to get ready for what amounts to a seismic shift in life insurance.

But that’s not what happened. The HEROES Act was shelved and it seemed like that was the end of the Section 7702 revision. Then, in the wee hours of 2021, the concept of more COVID-related support bills was back on the table and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 was swiftly adopted before the end of the year. In it, on page 4,923, is Section 205, which contains the revisions to the IRC Section 7702 rate. What seemed like an impossibility in March is now a reality as of 1/1/2021.

The immediate impact for Whole Life is that life insurers suddenly have an enormous amount of pricing flexibility. The change to the 7702 Rate essentially allows life insurers to devalue the guaranteed cash value growth of the policy by increasing premiums without violating CVAT/MEC limitations. Put another way, it pushes more of the benefits of Whole Life out of the guaranteed cash values and into the non-guaranteed dividends. That’s actually a good thing, despite how it sounds. For mutual companies, guaranteeing too much means that there’s less left over for distributable dividends. The change in the 7702 Rate allows Whole Life companies to appropriately balance guaranteed benefits and non-guaranteed benefits and, I would argue, that’s been out of whack (especially on short-pay products) for several years.

The practical implication is that short-pay products, in particular, are going to be dramatically repriced. Sell them (or buy them) while you can get them at today’s prices. For new products, companies will be able to offer similar (if not better) illustrated performance based on current dividends, but the guarantees will be much less attractive. We could also see companies introduce true 7-Pay Whole Life products because, finally, they’ll have enough pricing flexibility to pull it off.

More than anything else, the change in the Section 7702 rate just guaranteed Whole Life the flexibility it needs to ride out any economic environment. It ensures that Whole Life can maintain its central place in the pantheon – albeit at potentially higher prices. The future of Whole Life was secured by the intense lobbying efforts of the ACLI and Finseca, proof that these organizations are essential to the sustainability and longevity of our industry so that we aren’t victims of poorly written or ill-advised laws like the formerly hard-coded rates in Section 7702. Chalk this one up as a well-deserved and hard-fought win in a fight that almost no one knew was happening.

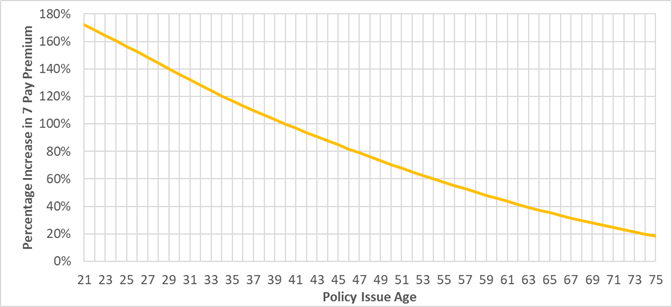

But, of course, Section 7702 also applies to Universal Life – and that’s where things get really interesting. The immediate and most obvious impact of the new rate is that maximum non-MEC premiums increase dramatically. Take a look at the chart below for a generalized impact on the maximum non-MEC / 7 Pay premium by the issue of the policyholder.

No matter what way you cut it, maximum non-MEC Premiums are going up. The sweet spot for accumulation Indexed UL sales is between 40 and 55, meaning an increase in maximum non-MEC premiums of between 100% and 60%. In other words, the changes to the 7702 Rate mean that a policyholder can put in 100% to 60% more premium per dollar of death benefit than before without triggering MEC status. Theoretically, that should make the policy more efficient at accumulating cash values when funded to the maximum non-MEC premium limits. That’s the advantage.

And at first blush, the gains in accumulation efficiency look huge. Assume a 45 year old Preferred Male on a $1M DB using GPT with an Option 2 switch and face reduction in the 8th year, the standard setup for an accumulation sale. I’m assuming a basic Indexed UL chassis without any multipliers or any other sort of funny business and illustrated at a level 5% rate. The old maximum non-MEC premium would be (in this example) $39,505 and would produce a year 50 IRR of 4.15%. The new maximum non-MEC premium is $72,951 and generates a whopping 4.49% IRR. The gains earlier in the contract are even more stark. At year 20, the old maximum non-MEC premium generates a 3.02% IRR and the new is nearly 3.9%. Clearly, Universal Life policies will become much more efficient, right?

Yes, but not in the way you think. There are two things making these products more efficient. The first is the obvious one. There is more money coming into the policy compared to the COI charges and that makes the product more efficient. Easy enough. The second is much less obvious and much more important one – reduced compensation per dollar of paid premium which, in turn, reduces policy charges. Take a look the table below showing how compensation changes under the new 7702 limits and then recalibrating the compensation to match the original amount.

| 7 Pay Premium | Death Benefit | Target | Commissionable % | Year 40 IRR | |

| Current 4% 7702 Rate | 39,505 | 1,000,000 | 21,110 | 53.44% | 4.15% |

| New 2% 7702 Rate | 39,505 | 541,528 | 11,432 | 28.94% | 4.49% |

| New 2% 7702 Rate | 39,505 | 541,528 | 21,110 | 53.44% | 4.26% |

After recalibrating the commission, the new, higher MEC premium limits tack on just 11 basis points of extra IRR. It’s something akin to a 0.25% change in the cap of an Indexed UL product, if you want to think of it that way. It’s fair to say that Universal Life policies will accumulate cash value slightly more efficiently under the new rules. That much is not in doubt and it’s an unmitigated benefit to the accumulation side of the industry. But how efficiently is a question of compensation, not tax rules.

That’s where things get really tricky. Compensation in Universal Life has long been based on Target premium linked to face amount. As accumulation products have become more prevalent, life insurers have been increasing Target premiums on accumulation products such that the current ratio of Targets on a death benefit-oriented product to an accumulation-oriented product is, ballpark, about 2-to-1. That’s understandable because clients buying accumulation products are putting as much premium as possible into the contract for a given dollar of death benefit, so higher Target premiums for those policies creates “fair” compensation.

However, the new changes to Section 7702 completely upend that relationship. Now, the maximum non-MEC premiums are increasing by (let’s say) 100% and, therefore, Target premiums have to be increased by 2x in order to generate the same commission for the agent for the same dollar of premium being put in to the policy. In that regime, it’s possible that some accumulation-oriented products might have four times the compensation of an otherwise identical death benefit-oriented product. In that scenario, it’s highly likely that the death benefit-oriented product will outperform the accumulation-oriented product, which leaves producers (and insurers) in a bind about which to choose.

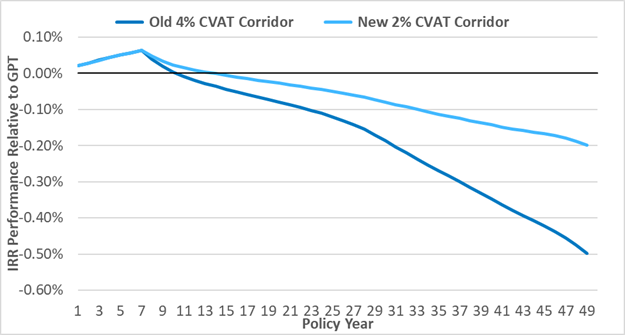

It gets worse. Many life insurers have been able to delineate between accumulation and death benefit sales by the death benefit option being illustrated and selected by the client at issue. Death benefit sales generally use a level (Option 1/A) death benefit and CVAT. Accumulation sales generally use increasingly (Option 2/B) death benefit and GPT. This split allowed companies to calibrate different compensation based on how the sale was being positioned. But under the new 7702 rates, the CVAT corridor shrinks significantly and the advantage of using GPT, with its lower corridor factors but higher required initial death benefit, is diminished. Take a look at the table below, which compares the IRR disadvantage of using CVAT versus GPT between the old and new rates.

In general, the gap shrinks by half. It’s entirely possible that folks begin to use Option 1 and CVAT for accumulation sales going forward because the loss of efficiency is more than made up for in terms of a simpler case design. And, as I’ve always argued, the loss of efficiency from using CVAT is because the client is carrying more death benefit, so in actuarial terms, it’s actually net neutral (or potentially a net benefit) to the client. Furthermore, using GPT requires a death benefit switch and reduction, something that works on the illustration but doesn’t (and shouldn’t) always happen in real life. That’s why I’ve always advocated for using CVAT over GPT, even in accumulation sales, despite the illustrated drag on performance. But with the new CVAT corridor, the drag is cut in half and it’s entirely possible that a lot of folks will switch from using GPT to CVAT for accumulation illustrations. If that’s the case, then the delineation between accumulation and death benefit-oriented sales based on death benefit option and 7702 test won’t be nearly as neat and clean as it is today.

The industry has taken Target premiums – and the stability of calculating 7702 minimum death benefits – for granted. With the changes to 7702, the competitive landscape for compensation is anyone’s guess. It’s possible that some companies maintain their current Target premiums because most of their sales are of the 20-pay or even Target premium variety, which will make them extremely competitive for overfunded scenarios. Other companies will feel like they have to change their Targets to reflect higher premium limits, which will skew their sales mix and their competitive positioning. Sorting this out is going to be a very tricky, problem-prone and iterative process. I think it’s entirely possible that companies move away from Target-based compensation and towards total premium based compensation or some combination of the two. The only thing that’s clear is that it’s going to have to change.

The other thing that’s going to have to change is product pricing. Life insurers price their products assuming a certain blend of ages, rate classes, face amounts and premium patterns. Actuaries are finely skilled in the talents of shaping profitability across all of those cells so that the aggregate meets the profitability standard for the life insurer. The fact that clients can now put 200% to 20% more premium per dollar of death benefit into their policies is going to wreak havoc on the pricing models at some insurers. Take, for example, an insurer that has extra margin baked into its COIs and funnels that extra margin into a fixed interest bonus. Under the new regime, the COI margin will pale in comparison to the payout for the fixed interest bonus. No bueno. And there are a lot of companies doing something similar or planning to do something similar to what I just described, especially in the world of AG 49-A. Companies may be left with no choice but to reprice their current products and change them in order for them to work under the new and higher limits which could, counterintuitively, result in less attractive illustrations than before for some products.

Where does all of this leave us? Think of it as short-term pain for long-term gain. The modifications to the Section 7702 rate are absolutely an unmitigated benefit for the life insurance industry. Companies selling Whole Life had to get relief in order to continue offer the powerful and valuable products that consumers want without losing their shirts in the process. All policies will now have more efficient cash value growth, which makes our products more attractive for folks using them for accumulation and distribution. The compensation model in the life insurance industry has been long due for an overhaul and now life insurers have a compelling reason to do it. All of these things are good. Really good. We should feel better – and more optimistic – about life insurance than ever. It is nothing short of a miracle that the life insurers, through the ACLI with involvement from Finseca, got this done.

But in the meantime, there are going to be a lot of procedural hiccups. Making the switch to new tax limits hasn’t been done in 40 years. The process is going to look different at every insurer and it’s going to be very clunky and disjointed. Because the new rules have higher limits than the old ones, it’s entirely possible that some companies keep issuing current contracts with the old limitations for many months before making the required updates whereas other companies do it quickly to capitalize on the new rules. Some companies can easily accommodate the change of rates from a technology standpoint, but other companies will have to dig into some old COBOL system to make it happen. On top of that, some companies are going to make product changes, some companies aren’t, and the competitive landscape is going to change in dramatic ways. There’s no sugarcoating it – the next few months are going to be a mess. But in the end, it’ll be well worth it.

1/6 Update – A few folks outside of our industry have misunderstood the Section 7702 changes to mean that, suddenly, people can “contribute” more money to life insurance than before. That’s not what happened. Contributions to life insurance have never been limited in the same way that, for example, IRA contributions are limited. Instead, life insurance contributions have only been limited by the ability of the person to be insured with a sufficient death benefit to allow a certain premium level. That rarely, if ever, is a problem except in extreme cases at both the bottom and top end of the market. Nothing about this rule change affects the ability for people to use life insurance for its accumulation and tax attributes, it just makes the life insurance policy slightly – and I mean slightly – more efficient than before for that purpose.

1/5 Update – A subscriber reached out to point out that Private Placement benefits from the higher contribution limits without the issues with Target premium. That observation is spot on. Private Placement compensation is already usually related to total premium and/or policy cash values so it will be unaffected by the higher premium limits.

1/5 Update – I’ve received a couple of questions regarding in-force treatment of policies. The new 7702 limits do not apply to in-force policies. The in-force policy will be limited by the contribution limits and corridor (if CVAT) stated in the original contract language. However, it seems as though material modifications to the policy, such as a face increase, could be treated as a “new” contract that gets the new and higher contribution limits. That still seems to be an open question and I’ll revise this answer once I know more.